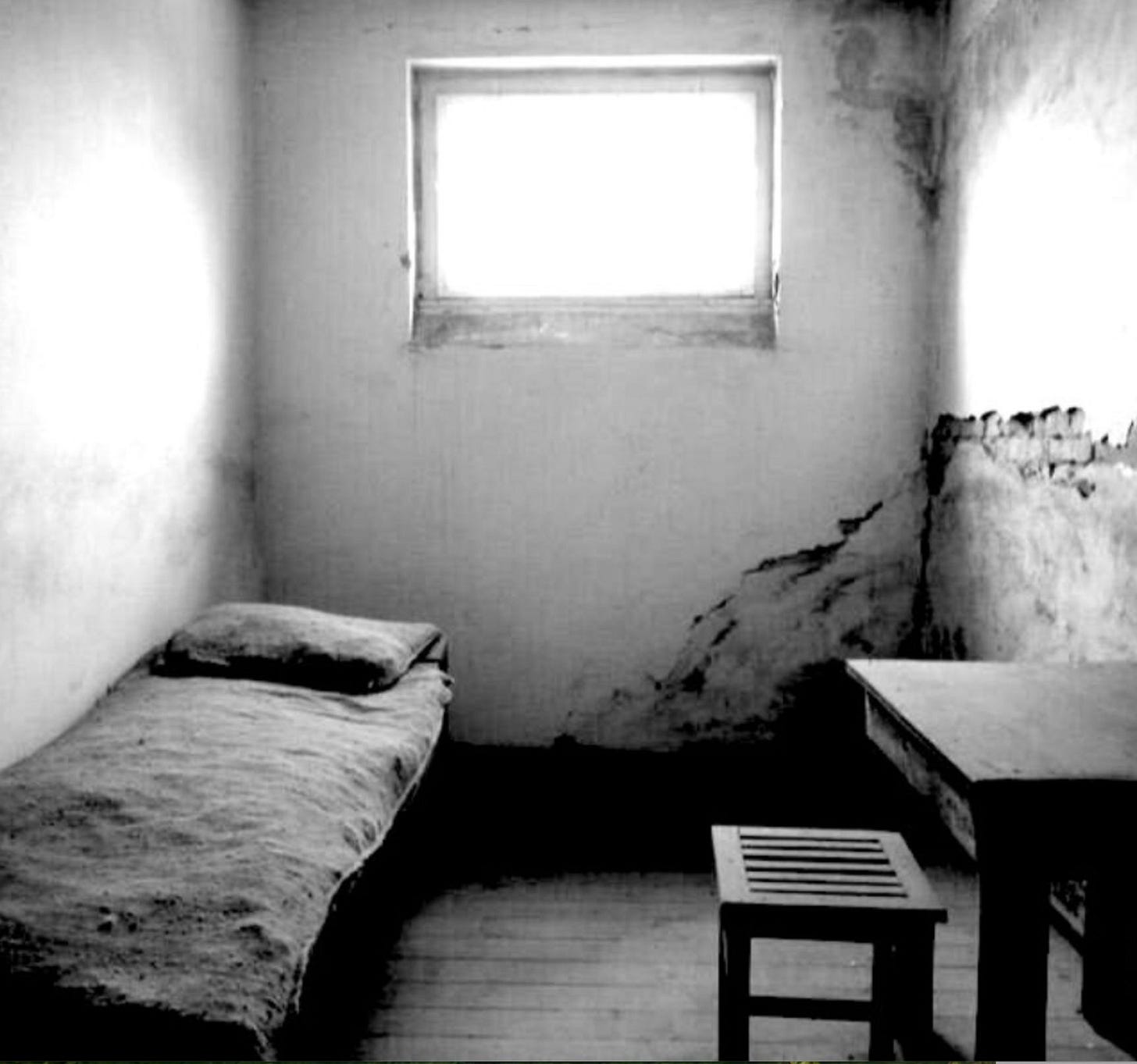

“By the way, a prison cell like this is a good analogy for Advent; one waits, hopes, does this or that—ultimately negligible things—the door is locked and can only be opened from the outside.”

-Dietrich Bonhoeffer

This week we read and discussed some of Bonhoeffer’s letters from prison during the season of Advent. Bonhoeffer touches on themes of suffering, grief, loss, and restoration, and sharing in the sufferings of God.

Here are the sections we discussed:

Letter to Karl and Paula Bonhoeffer, Dec. 17, 1943

My dear Parents,

There is probably nothing else for me to do than to write you a Christmas letter just in case. Even though it is beyond comprehension that I may possibly be kept sitting here even over Christmas, nevertheless, in the last eight and a half months I have learned to consider the improbable probable and by a sacrificium intellectus to allow those things to happen to me that I can’t change…

Above all, you must not think I will become despondent on account of this lonely Christmas; it will take its distinctive place forever in the series of diverse Christmases I have celebrated in Spain, in America, in England, and I intend that in years to come I will not be ashamed but will be able to look back with a certain pride on these days. That is the one thing no one can take from me…

Viewed from a Christian perspective, Christmas in a prison cell can, of course, hardly be considered particularly problematic. Most likely many of those here in this building will celebrate a more meaningful and authentic Christmas than in places where it is celebrated in name only. That misery, sorrow, poverty, loneliness, helplessness, and guilt mean something quite different in the eyes of God than according to human judgment; that God turns toward the very places from which humans turn away; that Christ was born in a stable because there was no room for him in the inn–a prisoner grasps this better than others, and for him this is truly good news. And to the extent he believes it, he knows that he has been placed within the Christian community that goes beyond the scope of all spatial and temporal limits, and the prison walls lose their significance.

Letter to Eberhard Bethge, December 18, 1943

Dear Eberhard,

You too must receive a Christmas letter, at least. I no longer believe I will be released. As I understand it, I would have been acquitted at the hearing on December 17; but the lawyers wanted to take the safer route, and now I will presumably be sitting here for weeks yet, if not months. The past few weeks have been more difficult emotionally than all of what preceded them…I am thinking today above all of the fact that you too will soon be confronting circumstances that will be very hard for you, probably even harder than mine…It’s true that not everything that happens is simply “God’s will.” But in the end nothing happens “apart from God’s will” (Matt. 10:29), that is, in every event, even the most ungodly, there is a way through to God. When, as in your case, someone has just begun an extremely happy marriage and has thanked God for it, then it is exceedingly hard to come to terms with the fact that the same God who has just founded this marriage now already demands of us another period of great privation. In my experience there is no greater torment than longing…I have become acquainted with homesickness a couple of times in my life; there is no worse pain, and in the months here in prison I have had a quite terrible longing a couple of times. And because I think it will be similar for you in the next months, I wanted to write you about my experiences in this. Perhaps they can be of some use for you… Above all, one must never fall prey to self-pity. And finally as pertains to the Christian dimension of the matter, the hymn reads, “that we may not forget / what one so readily forgets, / that this poor earth / is not our home”; it is indeed something important but is nevertheless only the very last thing. I believe we are so to love God in our life and in the good things God gives us and to lay hold of such trust in God that, when the time comes and is here—but truly only then!—we also go to God with love, trust, and joy. But—to say it clearly—that a person in the arms of his wife should long for the hereafter is, to put it mildly, tasteless and in any case is not God’s will. One should find and love God in what God directly gives us; if it pleases God to allow us to enjoy an overwhelming earthly happiness, then one shouldn’t be more pious than God and allow this happiness to be gnawed away through arrogant thoughts and challenges and wild religious fantasy that is never satisfied with what God gives. God will not fail the person who finds his earthly happiness in God and is grateful, in those hours when he is reminded that all earthly things are temporary and that it is good to accustom his heart to eternity and finally the hours will not fail to come in which we can honestly say, “I wish that I were home.” But all this has its time, and the main thing is that we remain in step with God and not keep rushing a few steps ahead, though also not lagging a single step behind either. It is arrogance to want to have everything at once, the happiness of marriage and the cross and the heavenly Jerusalem in which there is no husband and wife. “He has made everything suitable for its time” (Eccl. 3:11). Everything has “its hour”: [”]...to weep and...to laugh;...to embrace and...to refrain from embracing;...to tear and...to sew...and God seeks out what has gone by.” This last verse apparently means that nothing of the past is lost, that God seeks out with us the past that belongs to us to reclaim it. Thus when the longing for something past overtakes us—and this occurs at completely unpredictable times—then we can know that that is only one of the many “hours” that God still has in store for us, and then we should seek out that past again, not by our own effort but with God. Enough of this, I see that I have attempted too much; I actually can’t tell you anything on this subject that you don’t already know yourself.

Forth Sunday in Advent

What I wrote yesterday was not a Christmas letter. Today I must say to you above all how tremendously glad I am that you are able to be home for Christmas! That is good luck; almost no one else will be as fortunate as you. The thought that you are celebrating the fifth Christmas of this war in freedom and with Renate is so reassuring for me and makes me so confident for all that is to come that rejoice in it daily. You will celebrate a very beautiful and joyful day; and after all that has happened to you so far, I believe that it will not be so long before you are again on leave in Berlin, and we will celebrate Easter together once again in peacetime, won’t we?

In recent weeks this line has been running through my head over and over: “Calm your hearts, dear friends; / whatever plagues you, / whatever fails you, / I will restore it all.” What does that mean, “I will restore it all”? Nothing is lost; in Christ all things are taken up, preserved, albeit in transfigured form, transparent, clear, liberated from the torment of self-serving demands. Christ brings all this back, indeed, as God intended, without being distorted by sin. The doctrine originating in Eph. 1:10 of the restoration of all things, re-capitulatio (Irenaeus), is a magnificent and consummately consoling thought. The verse “God seeks out what has gone by” is here fulfilled…

By the way, “restoration” is, of course, not to be confused with “sublimation”!

Letter to Renate and Eberhard Bethge, Christmas Eve 1943

Dear Renate and Eberhard,

…I want to say a few things for the period of separation now awaiting you. One need not even mention how difficult such separation is for us. But since I have now spent nine months separated from all the people I am attached to, I have some experience about which I would like to write to you. Up to now, Eberhard and I have shared all experiences that were important to us and thereby helped each other in many ways, and now, Renate, you will be part of this in some way. In the process you should attempt somewhat to forget me as “uncle” and think of me more as the friend of your husband. First, there is nothing that can replace the absence of someone dear to us, and one should not even attempt to do so; one must simply persevere and endure it. At first that sounds very hard, but at the same time it is a great comfort, for one remains connected to the other person through the emptiness to the extent it truly remains unfilled. It is wrong to say that God fills the emptiness; God in no way fills it but rather keeps it empty and thus helps us preserve—even if in pain—our authentic communion. Further, the more beautiful and full the memories, the more difficult the separation. But gratitude transforms the torment of memory into peaceful joy. One bears what was beautiful in the past not as a thorn but as a precious gift deep within. One must guard against wallowing in these memories, giving oneself entirely over to them, just as one does not gaze endlessly at a precious gift but only at particular times, and otherwise possesses it only as a hidden treasure of which one is certain. Then a lasting joy and strength radiate from the past. Further, times of separation are not lost and fruitless for common life, or at least not necessarily, but rather in them a quite remarkably strong communion—despite all problems—can develop. Moreover, I have experienced especially here that we can always cope with facts; it is only what we anticipate that is magnified by worry and anxiety beyond all measure. From first awakening until our return to sleep, we must commend and entrust the other person to God wholly and without reserve, and let our worries become prayer for the other person. “With anxieties and with worry...God lets nothing be taken from himself.”

Letter to Eberhard Bethge, May 20, 1944

Dear Eberhard,

This letter is written just to you again; whether you discuss any of it with Renate is, of course, up to you. Today I would like to try and respond to the question that seems to me the most important one for you at present. At one point you asked what it meant that all your thoughts are occupied with your love for Renate, and the hard experiences of the last three weeks must have made that especially clear to you. To begin with, I must say that everything you told me moved me so deeply that I couldn’t stop thinking about it for the rest of the day, and I had a restless night. I’m infinitely grateful to you for that. It was a confirmation of our friendship, and besides it’s rousing all my life forces and fighting spirit again, making me defiant and clear…

You want to live with Renate and be happy, as you have the right to be. And you have to live, for Renate’s sake and for little Dietrich’s (and even big Dietrich’s)...However, there is a danger, in any passionate erotic love, that through it you may lose what I’d like to call the polyphony of life. What I mean is that God, the Eternal, wants to be loved with our whole heart, not to the detriment of earthly love or to diminish it, but as a sort of cantus firmus to which the other voices of life resound in counterpoint. One of these contrapuntal themes, which keep their full independence but are still related to the cantus firmus, is earthly love. Even in the Bible there is the Song of Solomon, and you really can’t imagine a hotter, more sensual, and glowing love than the one spoken of here. It’s really good that this is in the Bible, contradicting all those who think being Christian is about tempering one’s passions (where is there any such tempering in the Old Testament?). Where the cantus firmus is clear and distinct, a counterpoint can develop as mightily as it wants. The two are “undivided and yet distinct,” as the Definition of Chalcedon says, like the divine and human natures in Christ. Is that perhaps why we are so at home with polyphony in music, why it is important to us, because it is the musical image of this christological fact…? This idea came to me only after your visit yesterday. Do you understand what I mean? I wanted to ask you to let the cantus firmus be heard clearly in your being together; only then will it sound complete and full, and the counterpoint will always know that it is being carried and can’t get out of tune or be cut adrift, while remaining itself and complete in itself. Only this polyphony gives your life wholeness, and you know that no disaster can befall you as long as the cantus firmus continues.

Letter to Eberhard Bethge, July 16, 1944

God would have us know that we must live as those who manage their lives without God. The same God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34!). The same God who makes us to live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God, and with God, we live without God. God consents to be pushed out of the world and onto the cross; God is weak and powerless in the world and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us. Matt. 8:17 makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence but rather by virtue of his weakness and suffering! This is the crucial distinction between Christianity and all religions. Human religiosity directs people in need to the power of God in the world, God as deus ex machina. The Bible directs people toward the powerlessness and the suffering of God; only the suffering God can help.

July 18

“Christians stand by God in God’s own pain”—that distinguishes Christians from heathens. “Could you not stay awake with me one hour?” Jesus asks in Gethsemane. That is the opposite of everything a religious person expects from God. The human being is called upon to share in God’s suffering at the hands of a godless world. Thus we must really live in that godless world and not try to cover up or transfigure its godlessness somehow with religion…Being a Christian does not mean being religious in a certain way, making oneself into something or other (a sinner, penitent, or saint) according to some method or other. Instead it means being human…It is not a religious act that makes someone a Christian, but rather sharing in God’s suffering in the worldly life. That is metanoia [repentance], not thinking first of one’s own needs, questions, sins, and fears but allowing oneself to be pulled into walking the path that Jesus walks…

“Who Am I?” Poem (1944)

Who am I? They often tell me I step out from my cell calm and cheerful and poised, like a squire from his manor. Who am I? They often tell me I speak with my guards freely, friendly and clear, as though I were the one in charge. Who am I? They also tell me I bear days of calamity serenely, smiling and proud, like one accustomed to victory. Am I really what others say of me? Or am I only what I know of myself? Restless, yearning, sick, like a caged bird, struggling for life breath, as if I were being strangled, starving for colors, for flowers, for birdsong, thirsting for kind words, human closeness, shaking with rage at power lust and pettiest insult, tossed about, waiting for great things to happen, helplessly fearing for friends so far away, too tired and empty to pray, to think, to work, weary and ready to take my leave of it all? Who am I? This one or the other? Am I this one today and tomorrow another? Am I both at once? Before others a hypocrite and in my own eyes a pitiful, whimpering weakling? Or is what remains in me like a defeated army, Fleeing in disarray from victory already won? Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine. Whoever I am, thou knowest me; O God, I am thine!