Ends or Means?

Why did God become human? This is an old question and it is deceptively simple. The way we answer it will fill in answers to a lot of other questions that we aren’t directly considering.

It’s sort of like coming to a dirt road that has a bunch of ruts in it from other cars that have driven down it when the road was soft. Some of those ruts have been dug in so deep that you can easily get stuck. I once heard about a sign at the beginning of one of those old country roads that read: “Choose your rut carefully, you’ll be in it the next 4 miles.”

The same applies with this question. The way you answer it will lock you in to some things you didn’t necessarily intend when you began.

I think there are two broad categories of answers to the question: “Why did God become human?”

Instrumentalizing

Humanizing

The difference is simple. We’ve all had relationships that were instrumentalizing and hopefully we’ve all had relationships that were deeply humanizing. If someone is instrumentalizing their relationship with you they are using the relationship as a tool to get something else accomplished. The relationship becomes a means to some other end goal.

But in relationships that are humanizing the relationship itself is the end goal. There is no point to the relationship except the relationship itself.

These two categories can help us map the different answers that might be given to the question: “Why did God become human?”

Is the Incarnation a means to some other end (instrumentalizing)? Or is the Incarnation the end goal itself (humanizing)?

Instrumentalizing

Let’s take just one very common “instrumentalizing” answer: “God became human in order to die.”

This answer says that God became human because someone had to pay the price for sins. The cross does pay the price for sin. Scripture uses the language of a “ransom” (“The son of man did not come to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many” Mk. 10:45). So, of course sin is addressed in the the life of Jesus, but forgiveness of sins is not the end goal of the Incarnation, rather it is a by-product of God becoming human.

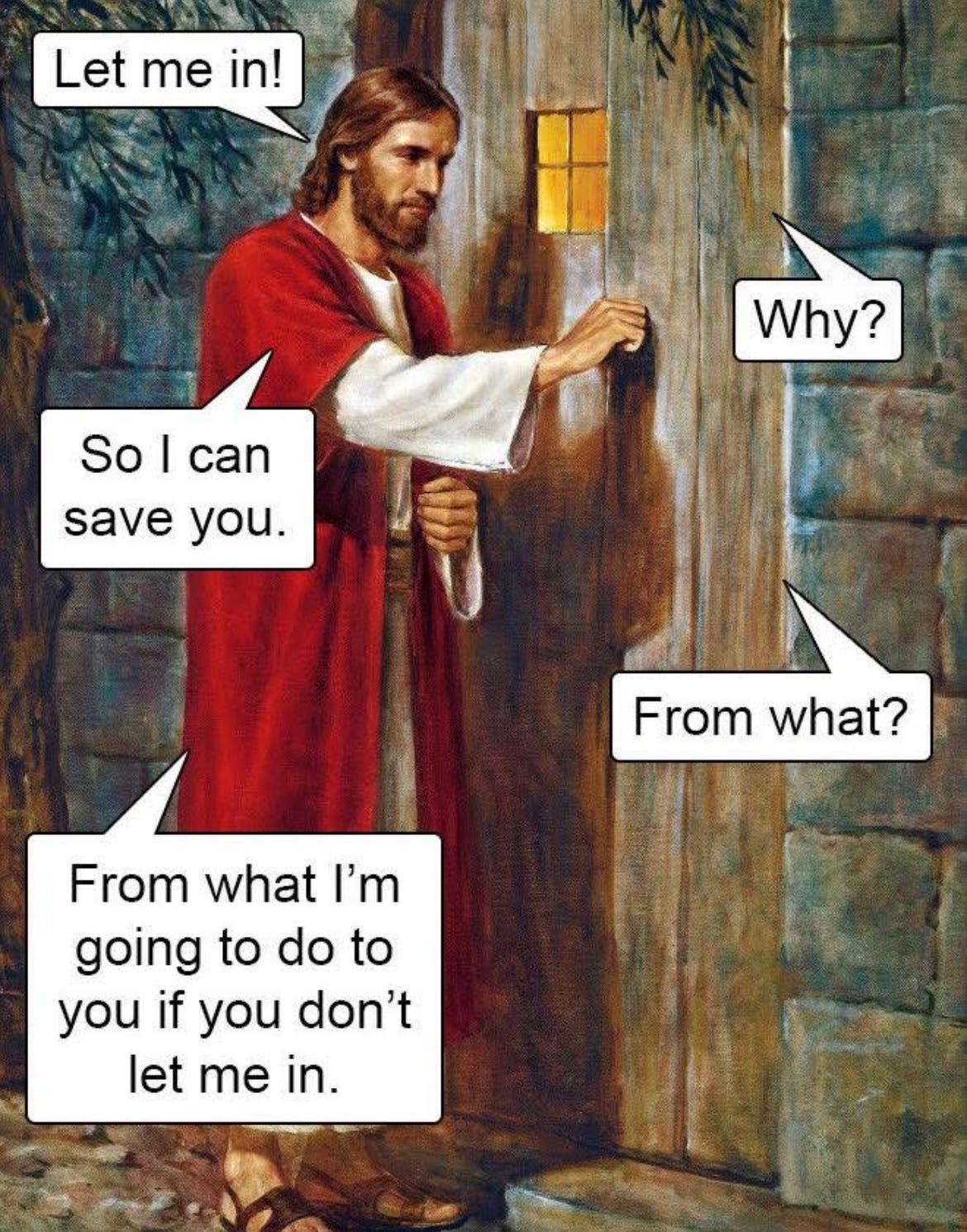

If you make “paying the price for sin” the end goal of the Incarnation, you will end up with some distorted views about God, the world, and humanity. Here’s just one example in meme form:

The reason for the Incarnation here is something like this: We need Jesus to save us from what the Father is going to do to us.1

Obviously the issues here are legion (in both senses). At bottom this would pit God against God. The Son is trying to save you from the Father. The Father turns his wrath on the Son instead of you in order to save you from what he was going to do to you. So there are deeply theological problems with this picture.

But this also instrumentalizes the Incarnation. It turns the Incarnation into a transaction between God and God as a means to accomplish salvation.

The Incarnation is the means to the end goal of balancing the Father’s scales of justice. His law has been broken and he demands a pound of flesh in return. So either Jesus gives it to him or we will.2

This “instrumentalizing” view (and others like it, even the more sophisticated ones) ends up making the Incarnation an afterthought for God. God created the world, but when things went south he had to send his Son in order to pull things back on track. In this case, the Incarnation doesn’t reveal anything to us about who God actually is or who we actually are. It’s merely a means to an end.

Humanizing (the end goal itself)

The second answer to why God became human insists that the Incarnation is the end goal itself. The Incarnation is the point of all creation. All things were created by Jesus, through Jesus, and for Jesus. The incarnation is the beginning and the end of creation. It is the first and last thought of God about his creation (see Col. 1, Jn. 1, Heb. 1).

In other words, God’s becoming human is not a tool that gets some other job done. It is the job done!

Maximus the Confessor puts it like this:

“The one who knows the mystery of the cross and the tomb, knows the reason of [all] things. The one who is initiated into the infinite power of the Resurrection, knows the purpose for which God knowingly created all.”3

According to Maximus the Incarnation was not a strategy to solve some other problem. The Incarnation is the purpose of the whole world. God created the world in order to becoming human.

This has a lot to say to us about how we relate to other. Our relationships with others are not tools for us to use to get something else accomplished. (Even if that something else is “getting them saved.”) Our relationships are never our means to some other end goal. Relationship is itself the end goal.4

Theosis: Becoming God

In the 4th century Athanasius of Alexandria wrote: “God became man so that man might become like God.”5

That can be a very jarring statement to hear for the first time. There are many ways to mishear this. What Athanasius does not mean is some sort of crude polytheism in which we all become gods who rule over our own private worlds apart from God.

Athanasius is saying that what God is by nature, he is making us to be us by grace.

This is the wonderful promise of the gospel: God wants to share his very life with you. He wants you and me and all creation to participate in the life that only naturally belongs to Father, Son, and Spirit. The early church had a term for this: “Theosis.” God is bringing us into his own life.

2 Peter 1:4 says, “[God] has granted to us his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature…”

If we use the language of “children of God” it might be a little more familiar. Who is God’s Son? He only has one by nature. His name is Jesus Christ. Jesus is the only begotten Son of God. And yet we dare to say that we, too, are called children of God! But we are not children by nature, we are children by grace.

In the Incarnation God has become human–what we are by nature–so that he can include you by grace into what he is by nature.

God wants to have the same relationship with you that he shares with Jesus. And Jesus wants you to have the same relationship with the Father that he has.

You and I can be called children of God only because we are in Christ. This is the meaning of Athanasius’s famous line.

But even Athanasius’s dictum can be turned into an “instrumentalizing” of the Incarnation. You could mishear Athanasius as saying that the Incarnation is a means to some other end.

We will mishear him if we think he means something like: “God became what was opposite and contrary to himself in order to make human beings something that is opposite and contrary to what they are.”

In other words, for God to make us “God” he would need to cancel out our human nature. The end goal would be to make us something non-human.

But that’s not what Athanasius means. We have to invoke Bonhoeffer one last time. In His Ethics he takes Athanasius’s famous line and tweaks it:

“Human beings become human because God became human.”6

He is not disagreeing with Athanasius. He’s saying the same thing, but in a more precise way. He’s saying that because the God we meet in the life of Jesus is God as human, then to become God in the way that this God is God is to become truly human.

Or as Bonhoeffer will say elsewhere:

“God as human being, and human being as God, must be held together in our thinking…We believe that Jesus the human being is God, and that he is so as the human being, not in spite of his humanity or beyond his humanity…”7

“It is finished”

So what does it mean to be truly human?

Think back to Genesis and the account of creation. In Genesis 1 God sets out each new day to create and fill the creation by saying, “Let there be...” He says it, it is, and it is good. Everything God creates is done in this fashion, except one thing: humanity.

On the sixth day of the week we find a change in the pattern. Rather than saying, “Let there be human beings,” God says, “Let us make human beings…” All the other bits of creation made on days one through five were simply setting the scene—the backdrop—for the play. Now, with the creation of humanity, we’ve come to the main action. This will be center stage: God’s project of making human beings in his image. And a project implies that it is not completed yet.

Two questions arise: 1) Why doesn’t God say, “Let there be a human being,” and 2) Has he finished his project yet?

We find the answer in John’s Gospel. John famously begins with an obvious allusion to Genesis: “In the beginning...” John is claiming (at least in part) that the life of Jesus is what Genesis is about. As you read through John you find that he has slipped in a multitude of echoes and allusions to Genesis.

On the day of Jesus’ trial and crucifixion John stresses that it was the sixth day of the week (John 19:14 “the day of Preparation for the Passover,” or as we call it “Good Friday”). Jesus, now beaten and bloodied, has been arrested and Pilate brings him before the hostile crowd. But Pilate announces something odd. He says, “Behold, the man,” “Ecce homo” (Latin) “ho anthropos” (Greek), or more accurately in English: “Behold, the human being.”

In Genesis God began his project of creating human beings on the sixth day and in John’s Gospel he completes it on the sixth day. Behold the human being. And then we get Jesus’ last words from the cross: “It is finished!”

The project that God began in Genesis is now being accomplished in Jesus, the truly human one. “Behold, the human being!”

Jesus, the one who pours himself out, who empties himself for the sake of others, is the image of God. This is the image God is conforming us to.

So again, why doesn’t God create human beings by saying “Let there be human beings”? Because to be truly human is to voluntarily lay your life down, to pour yourself out for the sake of others.

In other words, in order for the completion of God’s project of creating a human being to take place in you and me, we have to say, “Let it be.” God is patiently waiting for us to respond with our own, “Not my will, but yours be done.”8

These are truly human words precisely because they are truly divine words. The Spirit makes our words to be the words of Jesus. And oddly enough these human-divine words are words of prayer. As Robert Jenson says human beings are the “praying animal.”9

Of course, no one says it like this out loud. But this is often what people end up understanding the gospel to mean.

What’s really disturbing to me in this way of talking about the Incarnation is that it seems like the Father doesn’t care who is paying the price, as long as it gets paid. The end goal is that his holy wrath is satisfied. The Father is winding up to throw a lightning bolt at you like Shohei Ohtani, but the good news of the gospel is that the Son of God stepped in between you and the Father’s lightning bolt that was aimed at you. And because Jesus is also God the lightning bolt can’t completely destroy him. So he can be resurrected as proof that he was God.

This turns the incarnation into God playing a trick on himself so that we can be saved. But this is not the good news of God’s love for the world.

Quoted in Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology 2:24.

Andrew Root’s Relational Youth Ministry is great on this.

St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation, ch. 54.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Ethics, DBW 6, p. 96.

Bonhoeffer, “Lectures on Christology,” DBW 12, pp. 340, 354.

I’ve learned all this from Fr. John Behr. See his excellent book John the Theologian and his Paschal Gospel, or this lecture: “Which God Do You Believe In?”

Jenson, Systematic Theology 2:58.

Share this post