“Only good where evil was, is evil dead…

That alone is the slaying of evil.”

-George MacDonald, Lilith

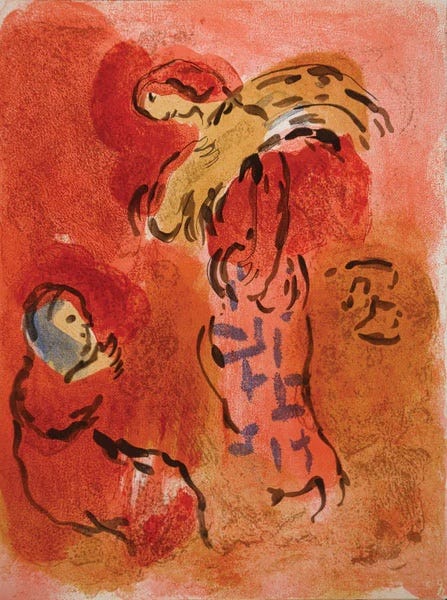

Naomi’s Plan: Risky and Risqué

Chapter 3 of the book of Ruth is the crucial episode in the story. The plot reaches its climax.1 But it is also the most disputed part of the book. It’s purposely written with ambiguous language that leaves a lot to the reader’s imagination.

In Ruth 3 Naomi devises a plan. She tells Ruth to bathe, anoint herself, and then get dressed. She is to go under the cover of night to the threshing floor where Boaz will have had a good meal and a good strong drink. After Boaz has laid down for the night, Ruth is to go “uncover his feet and lie down.”2 After that Ruth is to do whatever Boaz tells her to do.

Naomi’s plan is pretty straightforward. It doesn’t take much to know what she is insinuating: a sexual encounter is about to happen between Ruth and Boaz.

What does Naomi hope will happen? The story does not say. But when you take everything into account the most obvious answer is that Naomi hopes Ruth will become pregnant. This is sort of a plan of entrapment.

Biblical Bed Tricks

Why all this risqué material? The story is not lewd but it is racy.3 The ambiguous details of this scene are meant to cause the reader to make connections to two older stories from Genesis about the ancestors of Ruth and Boaz.

Both Ruth and Boaz have ancestors in their past who were involved in very similar stories—stories that Wendy Doniger calls “bed trick” stories. A “bed trick” is a very very common literary device where one character goes to bed with someone who is mistaken for someone else.4

First, Ruth’s ancestors. In Genesis 19:30—37 we read the story of the origins of the Moabite people: Lot and his two daughters. Lot’s two daughters have been widowed (two sons have died!) and they are worried about the future of the family. The older daughter concocts a plan to get Lot, their father, drunk so that they can sleep with him and hopefully conceive sons. It’s a “bed trick.”

The oldest daughter conceives a son and names him “Moab” which means “from my father.” According to the story Israel tells the Moabites are the product of incest. These are Ruth’s ancestors.

But the second “bed trick” story is from Boaz’s past. In Genesis 38 we find that Judah, one of the twelve sons of Jacob, leaves his family and goes to Canaanite country (maybe even worse than Moabite country).

While he is there Judah marries a Canaanite woman and has three sons: Er, Onan, and Shelah. Judah’s oldest son, Er, marries a Canaanite woman named Tamar. But Er dies. Judah then gives his second son, Onan, to impregnate Tamar. But then Onan dies. So, Judah promises Tamar that he will give his third son, Shelah, to her when he is old enough so that she can have a child. But Judah never makes good on his promise.

Tamar decides to take matters into her own hands. During the time of sheep-shearing, she disguises herself as a prostitute and waits by the road for Judah. Judah sees her but thinks she is a prostitute and so he has sex with her. But Judah cannot pay her, so she insists that he leave his seal and cord with her as collateral.

Tamar conceives and becomes pregnant. But Judah still does not know who she is. It’s a “bed trick.”

Later Judah finds out that Tamar is pregnant. He’s enraged and commands that Tamar be burned to death. But Tamar reveals that she has Judah’s seal and cord, showing that the son in her womb is actually Judah’s son.

Tamar, the Canaanite, gives birth to twins: Perez and Zerah. And as the book of Ruth will tell us, Perez is the great-great-great grandfather of Boaz.5

The Healing of the Past…

The similarities between the two “bed trick” stories (Lot and his daughters and Judah and Tamar) with the story of Ruth and Boaz are crystal clear. But the meaning is not in the similarities but in the differences. The story of Ruth and Boaz is set up as a “bed trick” but at the moment where the deception should occur, Ruth does not hide her identity with a trick, but comes out into the open about who she is what she desires. And Boaz—though he has had a strong drink like Lot—has his wits about him. He immediately devises a legal plan for marriage.

Ruth is like many of Israel’s own ancestors—except she is better! (And Boaz is also better than his grandfather Judah.)

The story of Ruth is the healing not only of Ruth’s past history but also of Boaz’s. It is the healing not only of the Moabites’ past, but the healing of the Israelite’s past—which is just as stained as the gentiles. Part of the promise of the book of Ruth is that the children of wayward families can set right their own family histories. Ruth and Boaz are expunging the shame of their ancestors.

But the story testifies to even more than that. The book of Ruth teaches us that all things in the past can be set right if God is who he says he is: the Alpha and the Omega.

Jesus of Nazareth, who is the son of Judah and Tamar, is also the son of Ruth and Boaz. But this means he is also the son of Lot and his daughters. Jesus is not ashamed to make these people his kin.

And Jesus is the one who not only does the will of God so that his family’s past history is made right by the actions of his historical life, but because he is the resurrected one, he is the Lord of all time–Past, Present, and Future. And he intends to set every episode of all human history right. All time is in his hands. This includes the time of Lot and his daughters, the time of Judah and Tamar, and all the past tragedies, traumas, and evils in our own lives.

In other words, Jesus doesn’t just want to tidy up the end of the timeline (which is all Boaz and Ruth can do), he wants to heal the entire timeline—even those events that are long gone and in the past. He doesn’t simply want a happy ending to a difficult story. He is resurrecting the entire story of human history.

The promise of the gospel is that in the end, at Christ’s coming, he will unmake and then remake all past tragedies, traumas, and evils. What was untrue to God’s will shall be made true.

We assume that because something is in our past it is over and done with. But just our past is is closed off to us does not mean it is closed off to him. He is the first and the last, the alpha and the omega, the beginning and the end.

We cannot access our own past, but he can. On our own we cannot make right what has happened, but he can make it so that all things are reconciled—even the traumas and tragedies of our past. And the promise of the gospel—the promise of the book of Ruth!—is that one day he will.

As Jordan Daniel Wood put it, “The scars of your past are not irreversible for him.”6

He will unmake all the evils in our past in order that his true will—his true creation—can come forth in its place.

But he will not not just erase it. Our God will unmake all evil and remake it so that his beauty, his goodness, and his perfect will shall be the truth of all past lies.

As George MacDonald elegantly put it his fairytale Lilith:

Annihilation itself is no death to evil. Only good where evil was, is evil dead. An evil thing must live with its evil until it chooses to be good. That alone is the slaying of evil.

Pun absolutely intended.

In (Re)reading Ruth William Tooman points out that when the Hebrew word “uncover” is used of a person, it almost always suggests being stripped naked. A sexual encounter is being hinted at here. But what do feet have to do with sex? Tooman explains, “Although there is vocabulary for male genitals…the Hebrew Bible mostly uses circumlocutions for them. Among the most common is the word ‘foot’ (regel). The ‘foot’ is the part of the body that is used to urinate (Judg 3:24; 1 Sam 24:4). Urine is ‘water of the feet’ (2 Kgs 18:27; Isa 36:12), and pubic hair is ‘hair of the feet’ (Isa 7:20). Judging from Deut 28:57 and Ezek 16:25, the euphemism seems to have originated as a shorthand for the part of the body that is located ‘between the feet.’ (We would say ‘between the legs.’) Though many interpreters object to this understanding of ‘foot’ in Ruth 3:4, I have not been persuaded that there is another plausible explanation of Naomi’s instruction. To my eye, those who object to this reading are attempting to explain away Naomi’s command rather than explain it. They are sanitizing the story to suit their own sensibilities” (pp. 93—94).

Other commentators agree with Tooman here. Robert Alter agrees that there is an “erotic tease of the narrative” (Strong as Death is Love, p. 72). Katharine Doob Sakenfeld says that “the overtones of a possible sexual encounter are heard” in these ambiguous words (Ruth, Interpretation, p. 54). And Edward Campbell writes, “It is simply incomprehensible to me that a Hebrew story-teller could use the words ‘uncover,’ ‘wing,’ and a noun for ‘legs’ [i.e. feet] which is cognate with a standard euphemism for the sexual organs, all in the same context, and not suggest to his audience that a provocative set of circumstances confronts them” (Ruth, The Anchor Bible, p. 131).

Chris E.W. Green, The Fire and the Cloud: A Biblical Christology, p. 291.

Quoted in William Tooman, (Re)reading Ruth, p. 97.

I’m drawing all this from William Tooman’s (Re)reading Ruth, pp. 97—106.

For more on this I recommend listening to this excellent conversation between Chris Green and Jordan Wood:

Share this post