“The last thing God needs is to be noticed.” -Chris E.W. Green

A field trip with the old rabbis…

Chapter four of the book of Ruth completes the primary movement of the story. It’s a movement from emptiness to fullness. Our story began with empty bellies—bellies that had no food and no children. It began with three deaths (Elimelek, Mahlon, Kilion), but it ends with three births (Obed, Jesse, David). This is the perfect symmetry of a story told by a master story-teller.

In many ways the conclusion of the book Ruth is unsurprising. Boaz is able to redeem Elimelek’s land and marry Ruth. Ruth conceives and has a son. And they lived happily ever after.

However, the reader is left with more than a few things to meditate on: what is Ruth’s connection to David? What is the meaning of Ruth’s name? And perhaps the strangest question of all is the fact that at the end of chapter four Ruth disappears from the story that bears her name.1

In considering these questions we take a field trip to the ancient synagogue and sit at the feet of the old rabbis. The rabbis have a wonderfully playful and imaginative way of interpreting the Scriptures—something we desperately need to recover. And the rabbis’ readings of Ruth are nothing if not imaginative and playful.2

I owe most of what follows to Avivah Zornberg, a brilliant Jewish reader of Scripture, and her pointing out these rabbinic readings.3

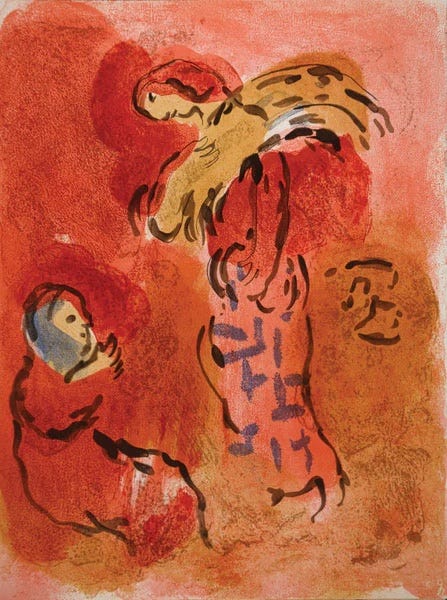

Stranger and Mother to Israel

Where Ruth ends David begins. This is true of the book of Ruth and the book of Samuel, but it is also true of their family tree. The last chapter of Ruth itself ends with a genealogy that ends with David.

In a midrash on the book of Ruth one of the rabbis brings up one of David’s most famous psalms, Psalm 119:

“At midnight I will rise to give thanks to Thee because of Thy righteous laws” (Ps 119:62).

Rabbi Phinehas commented in the name of Rabbi Eliezer b. Jacob: “A harp and a lyre were suspended over David’s head, and when the hour of midnight came he used to rise and play on them…” (Ruth Rabbah 6:1)

Midnight is David’s time for giving thanks to God. This is when he writes his psalms and plays his harp and lyre. But why does he do this at midnight? What connection is this rabbi making with the story of Ruth?

Ruth 3:8 tells us that Ruth sneaks into the threshing floor to “uncover the feet” of Boaz at midnight. This is when David’s great-grandparents were (at least) betrothed.4

David knows his story. Because of this midnight liaison between Ruth and Boaz, David rises at midnight to give thanks to God.

The rabbis continue (Ruth Rabbah 6:1):

Another interpretation: “Because of Thy righteous laws”: the laws [punishments] You brought upon the Ammonites and Moabites, and the righteousness [loving-kindness] You did for my grandfather and grandmother, for if he [Boaz] had uttered to her [Ruth] one single curse where would I have come from? But You did inspire him to bless her…”

David rises at midnight to give thanks God for his righteous laws. But the rabbi here splits them in two: the law on the one hand and God’s righteousness on the other.

The laws (or punishments) were brought against the Moabites to ban them. But the righteousness (or loving-kindness) was brought on David’s grandfather and grandmother, Boaz and Ruth.

What was the righteousness (loving-kindness) that God did for Boaz and Ruth? The law seemed to demand that Boaz curse Ruth at that midnight liaison, but God’s loving-kindness inspired him to bless her.

The rabbis envision David thinking through the possibilities here. It’s as if David is thinking, “I almost didn’t exist!” In fact, he’s saying that some readings of the law (Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s) would prohibit even King David from existing.

David is praising God at midnight because the blessing of his existence was so very close to being a curse. And David would never have “come.” He would never have “entered” the world.

The (dead) law would have condemned his grandmother and grandfather, but God’s righteousness, his loving-kindness, turned this curse into a blessing. Truly, though, the law has always had God’s righteousness and loving-kindness at its heart. And the rabbis know this.

David’s life is a miracle in more ways than one. This is why he wakes at midnight to sing his songs to the Lord—because his Great-Grandmother is Ruth the Moabite.

The meaning of her name…

Every interpreter of Ruth—almost without exception—loves to point out what all the characters’ names mean. Each of the names in the story have a sort of transparently obvious meaning: Elimelek means “My God is King,” Naomi means “Pleasant,” Mahlon and Kilion mean “Sickness and Destruction,” Orpah means “Nape of the Neck,” Boaz means “Mighty Man of Strength.”

But there is one name that is more opaque. What is the meaning of the name Ruth? Ruth’s name is ambiguous which has led to many, many suggestions of what it might mean.

Avivah Zornberg points out that at least one rabbi in the Babylonian Talmud provides a different meaning:

Ruth. What is the meaning of Ruth? R. Johanan said: “Because she was privileged to be the ancestress of David, who saturated the Holy One, Blessed be He, with songs and hymns.”

The Hebrew word for “saturate” is one of the closest sounding words to Ruth’s very odd name. The word “saturate” is not a word that is used often in the Hebrew Bible. But David does use it in one of his greatest hits—Psalm 23: “You anoint my head with oil, my cup overflows [is saturated].”

To be saturated is to be satiated. It’s a movement from thirst to being inundated with water. So, why would Ruth’s name mean “saturate”?

According to the rabbi quoted above, it is because David—the one who saturates God with praise—comes out of Ruth. She is the overflowing cup from which David is born. The songs that all of Israel will end up singing to God begin with Ruth. She saturates.5

As Zornberg puts it, “David was an unfolding of what was folded up in Ruth.”

The Disappearance of Ruth?

All this brings us to what is the most puzzling feature of the entire book of Ruth: Ruth ends up disappearing from her own story.

Ruth’s “disappearance” begins right at the moment her baby is born. Immediately the baby is in Naomi’s lap, not Ruth’s. The women all sing that a son has been born to Naomi, not Ruth. Ruth is also not mentioned in her own genealogy that closes the book.

But why? Is this the result of ancient Israel’s patriarchal society where women exist for the sake of men? Historically that may be true, but this text breathes with the breath of the living God. What can we make of all this?

Remember that Ruth is the one who saturates. Think of what happens when water saturates a plant. As the water soaks into the soil and makes its way down to the roots of the plant in order to fill it up with life, it seems to disappear from sight. It is not gone, though, it has moved to a more interior and vital position. In the same way, Ruth pours herself out into those around her, filling them up with her own love and life.

The rabbis have one last insight to offer us.

Zornberg points out that in the midrash the rabbis offer a sort of coda—an extension —to the end of the story of Ruth.

In the rabbis’ coda we’ve jumped ahead five generations to the court of King Solomon. We are at the scene of what will be his most famous moment, judging the case of the two mothers with the one baby:

Ruth the Moabite did not die until she saw her descendant Solomon sitting and judging the case of the prostitutes. That is the meaning of the verse, “And he placed a throne for the king’s mother”–that is Bathsheba; “And she sat at his right hand”–that is Ruth the Moabite. (Ruth Rabbah 2:2)

Ruth did not die until she saw her grandson Solomon judging this case. The text of 1 Kings 3 itself just says “There was a throne set for the king’s mother, and she sat at his right hand.” This obviously seems to be referring only to Bathsheba. But in a very imaginative and playful move the rabbi splits the verse to refer to two different mothers of King Solomon. He has Bathsheba sitting to the one side of throne and Ruth on the other.

Why is this the end of Ruth’s life? Why does she live to see this case in particular?

In this story from 1 Kings 3, two prostitutes come before King Solomon. Both of the women had babies, but one of the babies died during the night. Both women are claiming that the dead baby belongs to the other woman while the living baby belongs to them. There’s no way to know which woman is the true mother of the living baby.

So Solomon, in his wisdom, says that the living baby must be cut in two by a sword so that each woman can have half of the baby.

The one woman agrees to the plan. “Divide the baby,” she says, “Neither of us will have him.” But the other woman pleads for the life of the baby saying, “Give her the living child, but absolutely do not kill him!” And this shows Solomon who the true mother is. He just quotes the true mother: “Give her the living child, but absolutely do not kill him.” Then he adds, “That’s the mother.”6

The true mother would lay her life down for the sake of her baby’s life.

Here’s what the rabbis are suggesting: where does Solomon get the wisdom he needs to decide a case like this? It must be from his Great-Great-Grandmother, Ruth.

Ruth is the one who clings so tightly to Naomi that they share an essential identity. Ruth saturates Naomi like water in a plant. The baby can sit in Naomi’s lap without Ruth losing the baby. Ruth is the true mother. She can let go of the baby precisely because she is the true mother, just as the true mother does in the story of 1 Kings 3.

And here is Ruth, sitting beside her grandson, Solomon, flanking him with Bathsheba, witnessing the fruit of her womb.

Solomon has something of Ruth in him that allows him to know what to do. She has saturated him.

Ruth is happy to disappear in her own story. But she does it in the way God disappears in this story.

Have you noticed that God is not really an actor in the story of Ruth? Over and over again we read characters in the story ask God to do something that they themselves end up doing. Boaz prays that Ruth would find shelter in the shadow of God’s wing. But by the end of the story Ruth has found protection under the shadow of Boaz’s wing.

As Chris Green writes, “This story is incarnation.”7 God is fully embodied in the characters of this story. Their movements are God’s movements. Why? Because they have been saturated with his very life.

He is the water the plants need to truly live. It isn't so much that God has “disappeared” from the story, but that he has filled the entire story with his own life.

In this way Ruth shares God’s character: self-emptying love. The very heart of God is to pour himself out for the sake of others. As Philippians 2 says, “Though he was in the form of God, he did not count equality with God as a thing to be grasped, but rather he emptied himself by becoming a servant.” He saturates.

And when God empties himself it does not diminish him. God’s emptying is only ever a filling. This is what makes Ruth exactly like her God. God has no ego, and neither does Ruth. Ruth does not need to be center stage even in her own story, because her life has permeated and saturated all the other lives in the story.

“The last thing God needs is to be noticed.”8

Ruth is both a stranger to Israel and a mother to Israel. In fact, she can only become a mother to Israel by virtue of the fact that she is a stranger to Israel. Jesus is a stranger to Israel and to this world. The closer he comes to us, the stranger he feels. But it is not Jesus that is strange and alien. What we’ve made of our lives is what is strange and alien. When he comes close you realize that he is not strange. He is home.

Ruth is the strange one who makes a home for everyone she loves.

She has no ego. She saturates the way God does. Unnoticeable at first, but once you see it, you realize you’ve discovered that the deep heart of creation is incarnation.

The last chapter of Ruth does present a few thorny interpretive issues that we do not delve into. The first concerns a textual variant in Ruth 4:5 that can significantly shift the meaning of Boaz’s words. The second is about the legal implications of Boaz’s conversation with the other redeemer. If you are interested in knowing more you can comment on this post and we can have a discussion about it. I also would encourage you to read William Tooman’s excellent treatment of these issues in the last chapter of his book (Re)reading Ruth, pp. 123—124, 131—139.

You can find all these rabbinic readings of Ruth in the Midrash Ruth Rabbah.

Avivah Zornberg, “I am a Stranger: Becoming Ruth”

See our study last week regarding the implied sexual nature of this encounter:

My thanks to Sam Draper for helping me make many of these connections.

See Zornberg, “I am a Stranger: Becoming Ruth”

Chris Green, The Fire and the Cloud.

Chris Green, “The God of Ruth, The God of Naomi”

Share this post